INSPIRATION

Young Adventurers Chasing the Horizon

STORIES OF HUMANITY FROM FIVE PHOTOJOURNALISTS AND DOCUMENTARIANS

“Photography can put a human face on a situation that would otherwise remain abstract or merely statistical. Photography can become part of our collective consciousness and our collective conscience”

– James Nachtwey

Last year, over a million refugees and economic migrants crossed into Europe, fleeing violence in Syria, Afghanistan and Iraq, abuses in Eritrea, and poverty in Kosovo. This influx has sparked a crisis, with growing tensions and divisions in the EU over how best to resettle people, and a resurgence in the ugly side of nationalism.

But behind every sensationalist headline and hard-hitting statistic is a group of people in search of a better life – leaving behind everything they know, and in some cases risking their lives on a journey in search of safety, stability and prosperity. Their desire to flee war, poverty and discrimination is intrinsically human.

This is where photodocumentary and photojournalism is so important – finding the humanity amongst the politics and statistics, telling the stories of individuals. Seeing leading to understanding leading to empathy. Ron Haviv said it well: “This idea of helping the next generation is a very intrinsic part of photojournalism. We need to continue to build this new group of photographers that come in and tell these stories”. And so here we present the work of five of our favourite photographers, each with their own approach to storytelling, and each using image-making to inform, and to foster empathy and compassion. Visual arts with social purpose.

Banner image © Lucile Boiron

Lucile Boiron

L’Odyssée

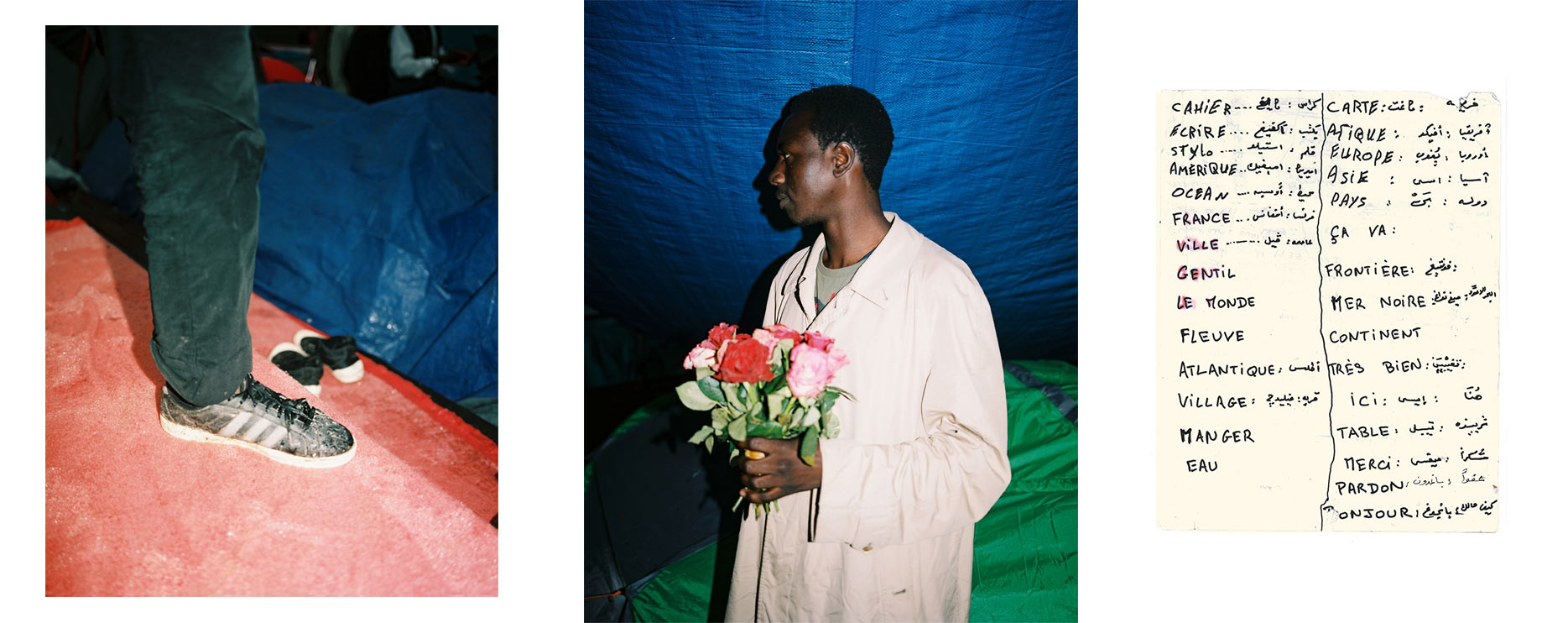

“In March of last year, almost by chance, I began visiting the camps where dozens of men and women would run aground daily after their long trek to a potentially better future. At first I felt incapable of taking the slightest photo. The state of emergency on the ground prevented me from thinking too much. I had to act, bring bread, water, blankets, and share a cigarette, listen, laugh from time to time; try to appease the hunger, the thirst, the cold. After all, what insight could I bring, a person who had been born on the “right side”? Then, Mohammed, a Sudanese poet, showed me photos of swollen bodies washed up on shore taken with his phone, portraits of friends who “had perished in the blue”. He asked me if I preferred photographing flowers. Its then that my eyes were opened and I saw them for what they really were:

young adventurers chasing the horizon.”

Images © Lucile Boiron – See more at www.lucileboiron.com

Demetris Koilalous

CAESURA: The Duration of a Sigh

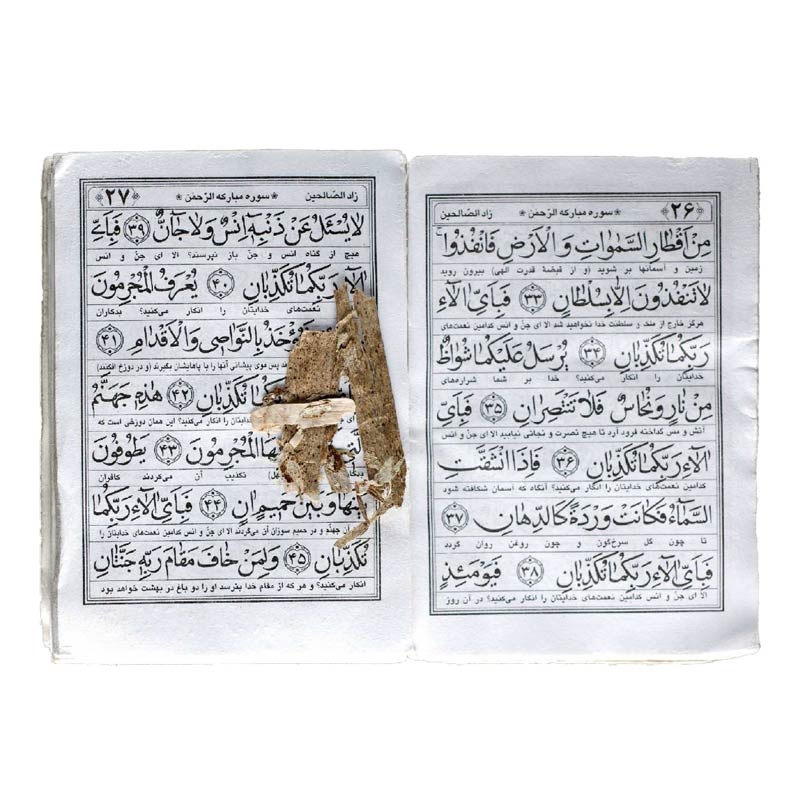

This project started in August 2015, and was completed in May 2016, after 13 trips to the borderlands of Greece. More than 150 personal objects were collected in-situ, along with the discussions and photographic exchanges I had with people I met along the way. The resulting project ‘Caesura’ is a collection of photographs about the transitory state of those people who entered Greece, after crossing the Aegean Sea – the infamous “death passage” – on their way from their homelands in Asia and Africa to the land of promise and hope, Europe. ‘Caesura’ is terminology for the brief silent pause in the middle of a poetic verse or a musical phrase, used in this context as a metaphor for a silent break amid two periods of loud ‘activity’ in one’s violent and distressed narrative.

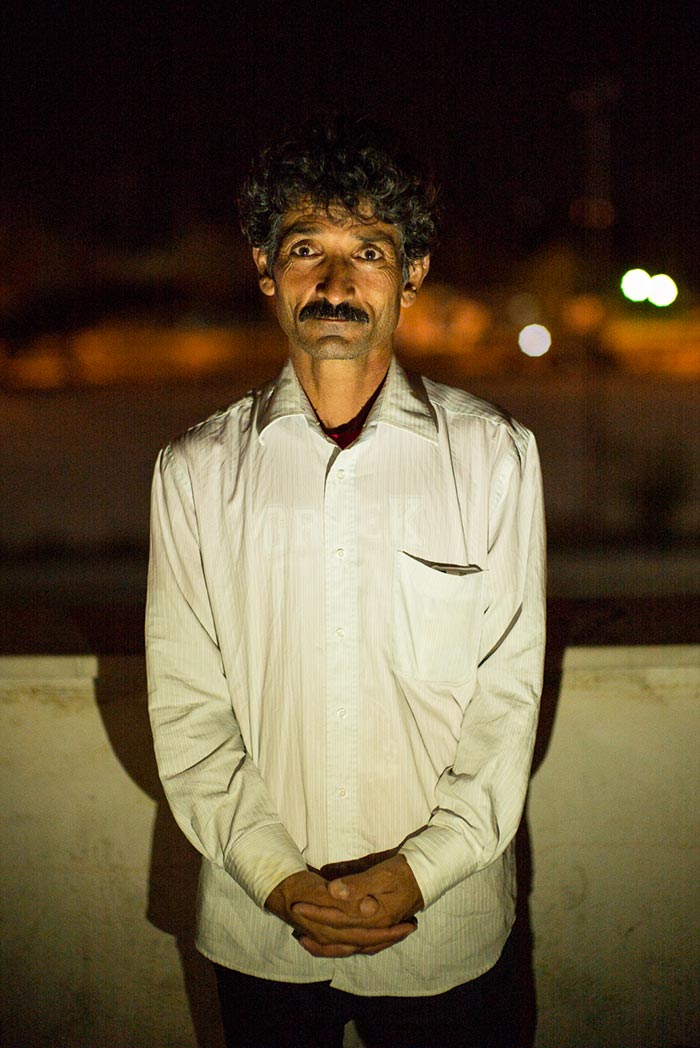

The characters in ‘Caesura’ are not a nameless mass, people among people. They have distinct identities and names, recognizable faces which unveil courage, determination and stamina, yet they are plunged into the melancholy of the temporary landscape in which they were caught: an intemporal space characterized by the gloominess of the border scenery. Remote and detached from the crowd, they place themselves – often unconsciously – in the centre of the narrative. My photographs attempt to raise questions about the human condition and identity; ultimately to raise questions about ourselves as viewers.

Images © Demetris Koilalous – See more at www.demetriskoilalous.com

Matteo Bastianelli

Souls of Syrians

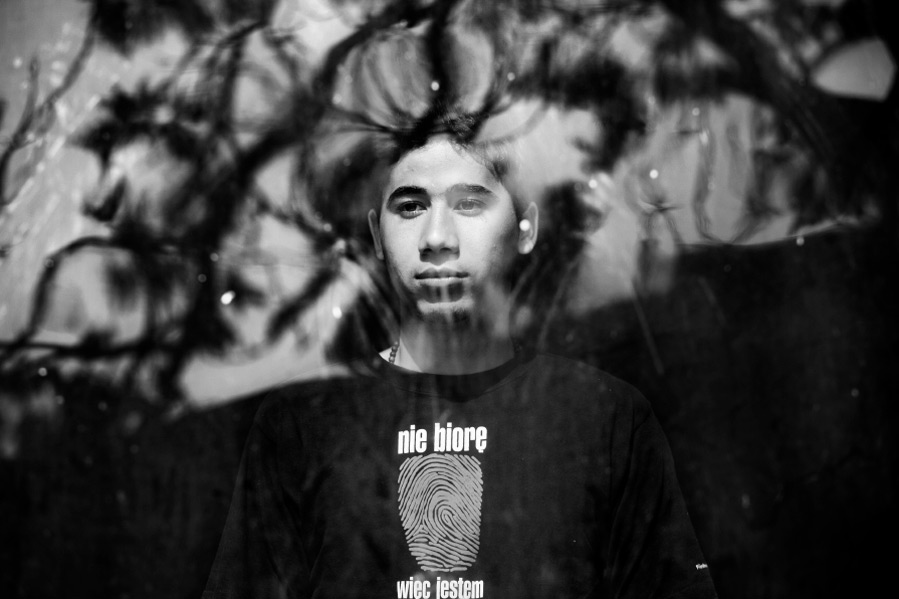

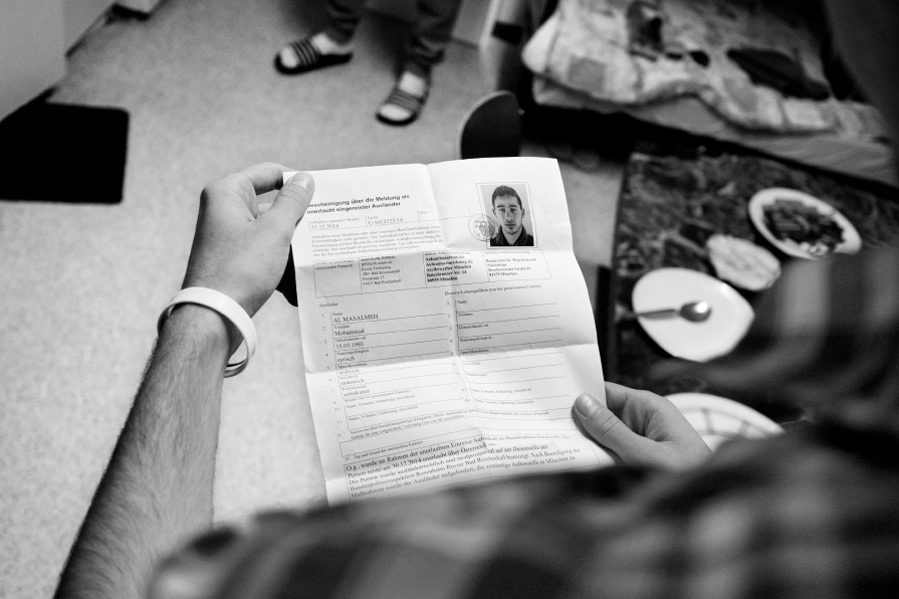

At the beginning of the Syrian Revolution in 2011, Mohamad was only 17 years old. While many young men decided to take up a rifle, he slung a camera round his neck and started accompanying his young cousin who was an activist in the revolt against President Bashar al-Assad. In January 2013, Mohamad’s cousin was killed by a sniper while working as a reporter for Al Jazeera in Syria. It was then that Mohamad decided to leave his family, to try to reach Europe.

His desire to become a photographer caused me to approach him, and it was then that I decided to tell his story.

He has with him images of his tormented nation, and the horror he saw impressed in his eyes. And yet he is still full of hope. After one year in the Harmanli refugee camp in Bulgaria, Mohamad travelled on his own, paying a human smuggler who showed him the route to cross borders. He then took a train and finally joined his cousin Hany in Warstein, Germany, in January 2015.

After more than a year of waiting, Mohamad was finally granted asylum. He hopes to enroll in university and start a career as a reporter. His dream however, is to return home once the conflict has ended. To return down the road of adventure, that leads to an uncertain future for the Syrian people.

Images © Matteo Bastianelli – See more at www.matteobastianelli.com

Mioara Chiparus

Not Wanted

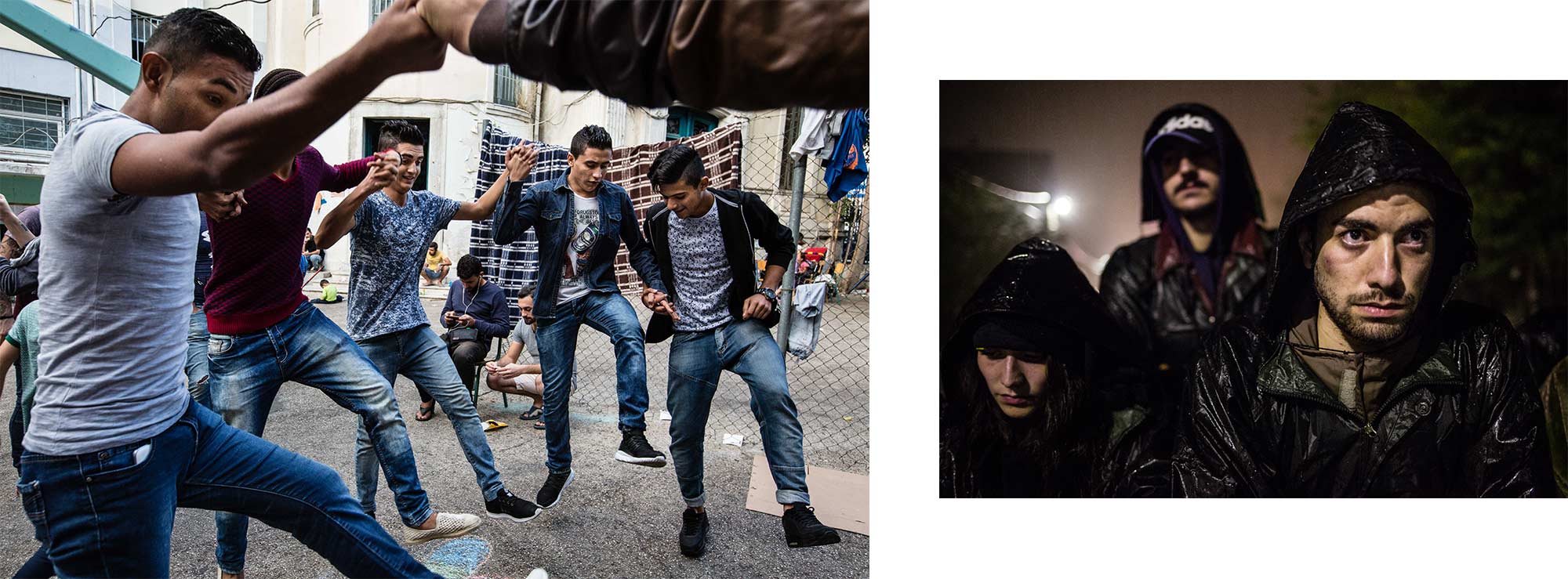

From 1938 to 2001, Ellinikon was Athens’ international airport. After it closed as such, trade fairs and congresses were held in the complex so that the buildings would not remain empty. When increasing numbers of refugees started reaching Greece, the former airport was given a new role as a refugee camp. I now go regularly to the airport to get an impression of the current situation, and to give faces to the predominantly Afghan refugees.

“‘When will the borders open?” and “Why did they close the borders?” are the main questions the Afghan refugees housed in the old airport building in Athens ask me when I visit them. Children and their parents and grandparents are trapped in limbo in the departure terminal – ironically a place which previously had facilitated transit to final destinations. They have been waiting for more than eight months for the borders to open so that they may continue on their journeys.

Despite the fact that Greece finds itself in economic turmoil and facing an uncertain future, many Greek citizens have made tremendous efforts to help the refugees. However, there is a vocal minority in Greece who resent the refugees and fear the consequences of this unprecedented influx.

Each time I visit the camp I see the peoples’ hopes diminished. Their living conditions are tough and their fates are being decided by others. They face an uncertain future and are aware of the fact that the mood in Europe is gradually turning against them.

Images © Mioara Chiparus – See more at www.mioarachiparus.com

Kristof Vadino

Are We Human?

Lesvos, Greece. At the beach of Skyminea up to 10,000 refugees arrive daily in the summer of 2015. The little plastic boats coming from Turkey should contain no more than 20, but smugglers put 50 to 60 refugees inside, making the passage very prone to accidents and death. After a four hour passage they’re frozen and exhausted, having had to navigate without any experience.

In the informal camp of Kara Tepe, Lesvos, refugees listen carefully to a list of names being proclaimed. The lucky ones can register and take a boat to Athens the following day. Others have to wait an indefinite time. This informal camp is run by NGOs and refugees.

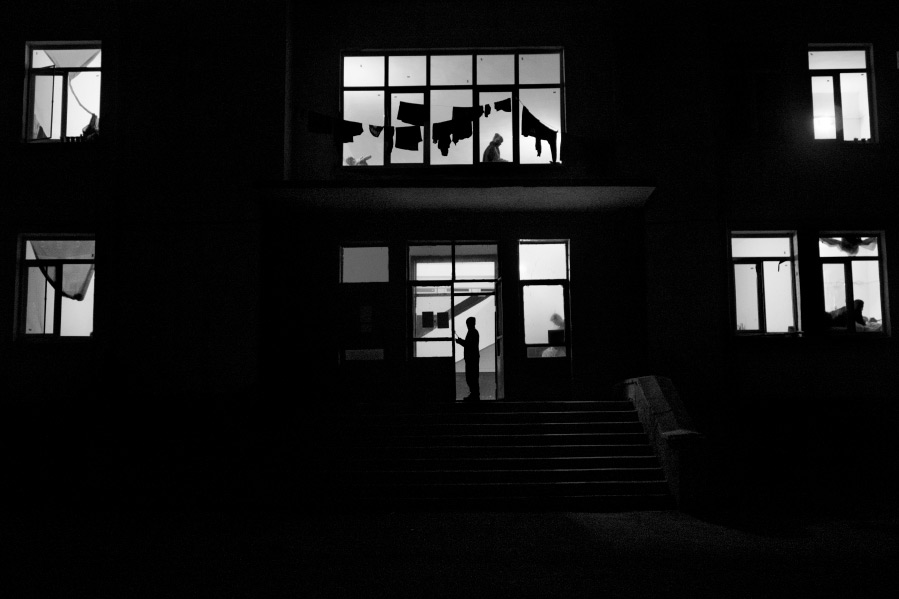

Athens, Greece. Syrian refugees occupy an abandoned school in the center of Athens. Some have waited for over 7 months to get registered for the relocation scheme. After admission it takes another year to move to another EU country.

Since August 2015 I’ve documented the refugee routes towards the EU. The stories are published in De Standaard newspaper and by Doctors of the World. I continue photographing the refugee crisis, as I think it is essential for our future how we deal with this. As political manfestations of hatred and racism are growing in the EU, and as political discourse is pointing at the otherness of the refugees, I want to show that the refugee may be different from us, but that at the same time he or she is just like us. We should organise the refugee crisis in a human way, which is not the case now. Some EU countries are at this moment violating the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, the Convention of Geneva and European directives on migration.

Many Refugees asked me: “Are we human? Or are we animals?”

Images © Kristof Vadino – See more at www.kristofvadino.com