INTERVIEW

Fragility and Resilience

WITH THIBAULT GERBALDI

AN INTERVIEW WITH THIBAULT GERBALDI

“Fragility isn’t weakness, it’s exposure to change. Resilience isn’t abstract heroism, it’s the capacity to adjust, to endure, and to keep meaning intact.”

Thibault Gerbaldi, a second-time Life Framer winner, won 1st Prize in our recent Humans competition with a stunning, almost entrancing environmental portrait of members of the Dayak in Borneo – one that judge Bronwen Latimer praised for being “striking in its subject, its composition, its detail and its emotional intensity”. Shot on one of his many travels, but with an aesthetic quality that stands out against much of his other work, we were keen to know more: how the image came about, whether it signals a new direction, how he’s preparing for an upcoming outdoor exhibition in Paris, and of course, what advice he’s pass on to his future self or others…

You can see Thibault’s outdoor exhibition, Fragilités et Résiliences, at Jardin du Luxembourg in Paris from 21 March to 19 July 2026.

THIBAULT’S WINNING HUMANS IMAGE: RITUALS OF BORNEO

Thibault, congratulations on winning our Humans competition! Please introduce yourself to the reader in a few words…

I’m Thibault Gerbaldi, a Franco-American travel and documentary photographer. I photograph people and the environments that shape their lives, often in places where traditions, work, and climate pressures coexist. My work sits between portraiture and landscape, with a focus on human dignity, everyday gestures, and what connects cultures beyond appearances.

This isn’t your first time winning Life Framer. What keeps you coming back for more?

I did – I won the Black & White competition at the end of 2023, and it really stayed with me.

I keep coming back because Life Framer’s themes are both precise and open: they push me to edit differently and to revisit my work with fresh eyes. I also like the spirit of the platform — a real diversity of voices, and a sense of sharing work with intention, not just for visibility.

Your winning image is stunning, but also quite different from a lot of your other work, particularly in the color treatment. Can you tell us a little more about the shot and the circumstances behind it? Is it indicative of how your style and approach is changing?

My intention was to accentuate the timelessness of Dayak traditions. Even though the photograph was made today, I wanted it to feel anchored in something older, to suggest the weight of ritual, transmission, and collective memory.

That’s why I chose a faded, almost sepia-toned black and white. It strips the image back to gesture, texture, and presence, and it creates a more cinematic atmosphere, as if the scene could belong to another era.

I wouldn’t say my style is fundamentally changing, but this image is indicative of something I’m leaning into more: being more deliberate in post-production when it serves the meaning. I spent a lot of time on the edit to find the right balance between documentary fidelity and the emotional tone I felt on the ground.

And how did that whole experience, of visiting an indigenous group from Borneo, come about?

I was deeply moved by the story of this community — and by its young leader, Poyang, who is only 33. He’s built something rare: a dance and arts school that helps preserve Dayak traditions while also sharing them openly with others.

His studio has become a small cultural hub. He trains children and young adults from across the island, including students and workers who’ve migrated to South Kalimantan. Many come from different regions, but they share the same desire: to reconnect with indigenous culture, learn its rhythms and gestures, and keep it alive through practice, not nostalgia.

Meeting him, and seeing that transmission happening in real time, is what made the whole experience feel so powerful.

You talk about “playing with the contrasts between what appears strong and what is truly resilient”. What do you mean by that?

What I mean is that appearances can be misleading. Through travel, I’ve often met people living in conditions that might look “vulnerable” from the outside — defined by what they lack. But on the ground, what struck me was often the opposite: the strength of community ties, ingenuity, transmission, and the ability to preserve continuity while adapting to reality. Fragility is real, of course, but it almost always coexists with something very concrete: a quiet, daily resistance.

Landscapes led me to the same conclusion. We tend to think of them as solid and permanent, yet they’re constantly shifting — through erosion, fractures, cycles, melting ice, desert expansion, or changing shorelines. Photographing them is a way of capturing impermanence, sometimes visible in an instant, sometimes only when you step back.

Over time, I’ve come to see that fragility and resilience belong together. Fragility isn’t weakness, it’s exposure to change. Resilience isn’t abstract heroism, it’s the capacity to adjust, to endure, and to keep meaning intact. Climate change often links the two, accelerating transformations and placing new pressure on communities. My work stays in that tension, and tries to show how what looks strong isn’t always what truly holds, and what looks fragile is often what lasts.

As an extensive traveler – visiting Greenland, Namibia, Peru, Mongolia, the US and of course Borneo amongst many others – what has been the most fulfilling trip you’ve had so far?

It’s a tough question, because each place has given me something completely different – a culture, a rhythm, a way of seeing.

If I had to pick the most fulfilling, I’d say India. India is so vast and diverse that one trip feels like an invitation to return and discover entirely different worlds. But what stayed with me most was how often I felt a quiet sense of gratitude there. Day after day, I was moved by the smiles and the dignity of people who, from the outside, might be seen as vulnerable. It was a powerful lesson – human, visual, and emotional all at once. And photographically, it’s an endless gift: color, texture, light, and layers of life everywhere you look.

Another trip that really mattered to me was a short journey to Iceland two years ago. It changed my relationship with weather. With my guide, Brynjar, I learned to stop seeing difficult conditions as an obstacle, and instead treat them as part of the story, a tool to create mood and atmosphere. In a strange way, I’ve rarely been as happy as I was to be out there, in the rain and cold, in the middle of summer.

Perhaps you could share and describe a couple of your favorite shots from that trip?

One that stays with me is the sadhu in Varanasi at dawn, standing on the ghats with the river fading into mist and the boats lined up behind him [The Sadhus of the Sacred City, banner image]. I loved how timeless it felt: a quiet moment of presence in a city that carries such spiritual weight. I actually used that image as the cover for my exhibition because it captures what I felt there – intensity, calm, and a sense of something larger than the everyday.

Another favorite is the man preparing betel leaves in a narrow alley in Varanasi [A Bite of Tradition, below]. It’s a simple scene, but visually it was incredibly rich: the tight space, the layers of texture, and the way every object has its place. For me it says a lot about India – this ability to create order, color, and ritual in the middle of density.

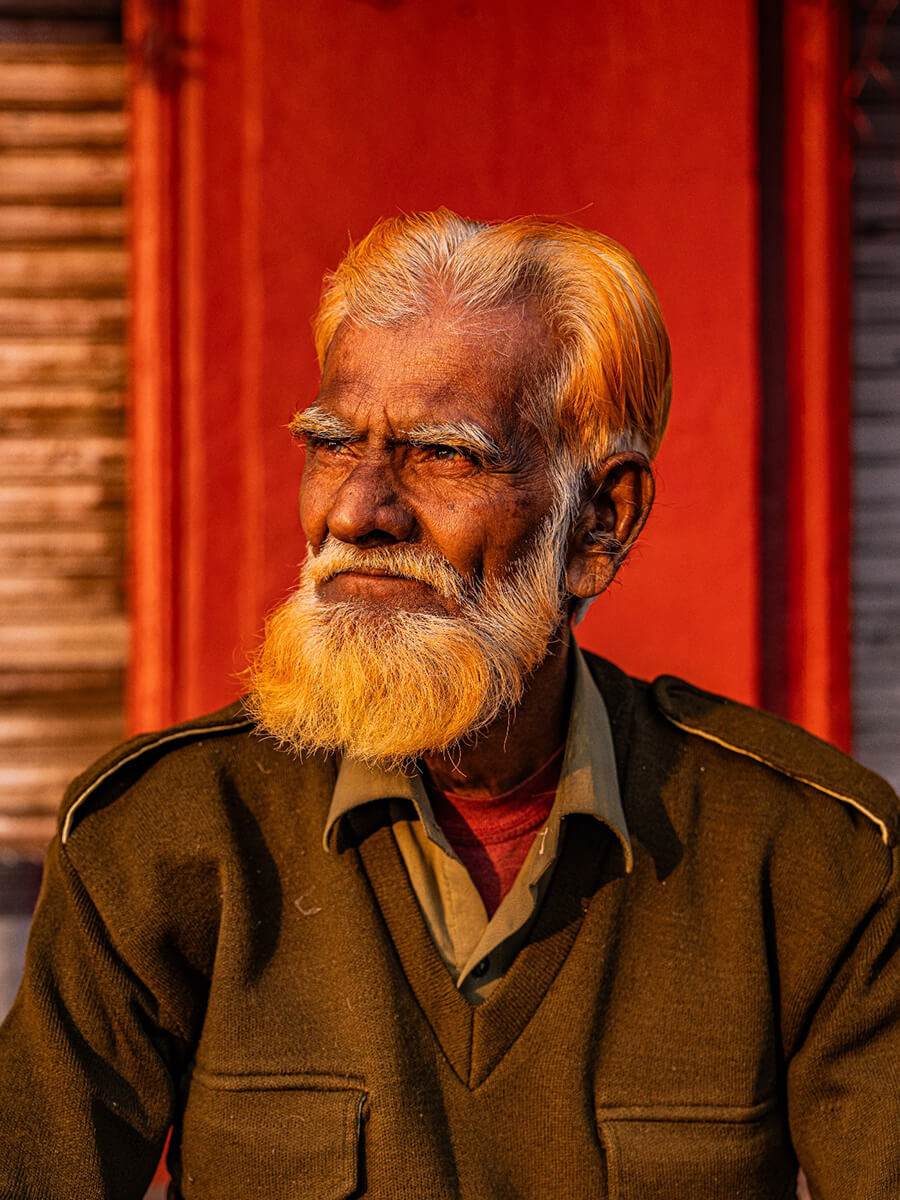

I also love the barber shop portrait [below]. The colors, the worn walls, the mirrors, the light – everything felt like a small time capsule. The barber had been practicing for decades, and the scene had that feeling you get in India sometimes, where you turn a corner and it feels like you’ve stepped into another era. Not as nostalgia, but as continuity.

And from Iceland, I would pick the black and white storm seascape [below]. It was taken after heavy weather on an iconic beach in the south, and I remember being struck by how the darkness wasn’t empty, it was alive with movement and texture. I love abstract art, and that image reminded me of Pierre Soulages: the idea that darkness can carry light, and that harsh conditions can become a mood rather than a problem.

You have an exhibition in Paris, starting in March, at the Jardin du Luxembourg and titled Fragilités & Résiliences (Fragilities & Resiliencies). How did that come about, and how would you describe it to a reader who may be interested?

The exhibition came out of the project itself, not the other way around. Fragilités & Résiliences started before I ever thought about showing the work publicly. During an interview a few years ago, I tried to put into words what really drives me to photograph, and one idea kept coming back: empathy. The need to connect with people, to understand lives and cultures, and to share that experience through images.

In parallel, I realized I was equally drawn to landscapes where nature is visibly at work: sometimes dramatic, sometimes almost silent, but always changing.

At that point I had already self-published several books, usually built around a place or a journey. Over time, I wanted to step back and build something more transversal – a project crossing countries and continents, linking very different photographs through a single perspective. That’s where the theme became clear: placing side by side the fragility of environments – their ruptures and transformations – and the very concrete ways communities adapt, through daily gestures, rituals, skills, and relationships.

When I later applied to exhibit on the railings of the Jardin du Luxembourg in Paris, the intention was already to make that synthesis accessible: a clear outdoor journey where portraits and landscapes speak to each other image after image. For a reader discovering it today, I’d describe Fragilités & Résiliences as a visual dialogue between appearance and reality – what seems strong but can shift quickly, and what seems vulnerable yet holds through dignity, continuity, and the quiet strength of adaptation.

THIBAULT’S FAVOURITE SHOT: A BITE OF TRADITION

THIBAULT’S FAVORITE SHOT: BARBER OF THE PAST

THIBAULT’S FAVORITE SHOT: WHISPERS OF THE STORM

How have you had to think about arranging an exhibition in an outdoor rather than gallery space?

Arranging an outdoor exhibition is a completely different exercise from a gallery show, because you’re not controlling the conditions, you’re working with them. At the Jardin du Luxembourg, the audience is moving, the light changes constantly, and people might stop for ten seconds or come back several times over the course of weeks. So the sequence has to work in fragments: each image needs immediate impact at a distance, but also enough depth to reward a slower second look.

The large format is key. Outdoors, scale becomes the first invitation – a color, a silhouette, a gaze that interrupts someone’s walk for a moment. But you also have to think about rhythm: alternating portraits and landscapes, building visual bridges from one panel to the next, and using strong chromatic or graphic connections so the exhibition remains readable even if you enter it in the middle.

What I love about this setting is how open the reception becomes. There’s no barrier, no ticket, no “proper” way to look. The photographs mix with daily life: commuters, students, families, tourists. The same image can feel different depending on the time of day, the weather, or the mood of the viewer. In a way, it’s less about a single curated “reading” and more about creating a space where people can pause, travel mentally, and maybe reconnect, briefly, with lives and places far from their own.

Is there a bucket list destination you’d love to visit next?

It’s a difficult question, because the list keeps growing. Bangladesh is very high on it, for the intensity of daily life and the photographic stories I feel are there. I’d also love to return to India, because it’s a country you never really finish discovering. Mongolia is calling me back too, especially the far north to witness the reindeer herders and seasonal migrations. And Ecuador is another place I’d love to explore – the mix of landscapes and cultures feels incredibly rich.

What’s the best piece of advice you’d pass on to your younger self if you could?

I wouldn’t change my answer from my last Life Framer interview: I wish I’d started taking pictures earlier. I traveled extensively when I was younger, and I still feel a small regret not having captured more of those moments through photography. If I could give little Thibault one piece of advice, it would be: don’t wait so long before pressing the shutter.

And finally, good luck with the exhibition Thibault! Anything else you’d like to add?

Thank you so much. If any of your readers find themselves in Paris this spring, I’d love for them to experience the exhibition in person at the Jardin du Luxembourg. Because it’s outdoors and freely accessible, people can simply stumble upon it, return, and let the images settle over time.

My hope is simple: that it sparks emotion, but also reflection, and maybe a few conversations. If someone walks away feeling a little more curious about a place, a culture, or a life they didn’t know, then the photographs will have done what I hoped they could do.

EXHIBITION SHOT: FRAGILITÉS ET RÉSILIENCES, LE JARDIN DU LXEMBOURG, PARIS

All images © Thibault Gerbaldi

See more at www.tgcrossroads.com and follow him on Instagram: @tg_crossroads.