INTERVIEW

Serenity in the Noise

WITH LIAM MAN

AN INTERVIEW WITH LIAM MAN

“Empty bottles, food wrappers and eroded paths made it clear that many landscapes had been reduced to simple backdrops for selfies and travel photography. I wanted my images to stand apart from this noise.”

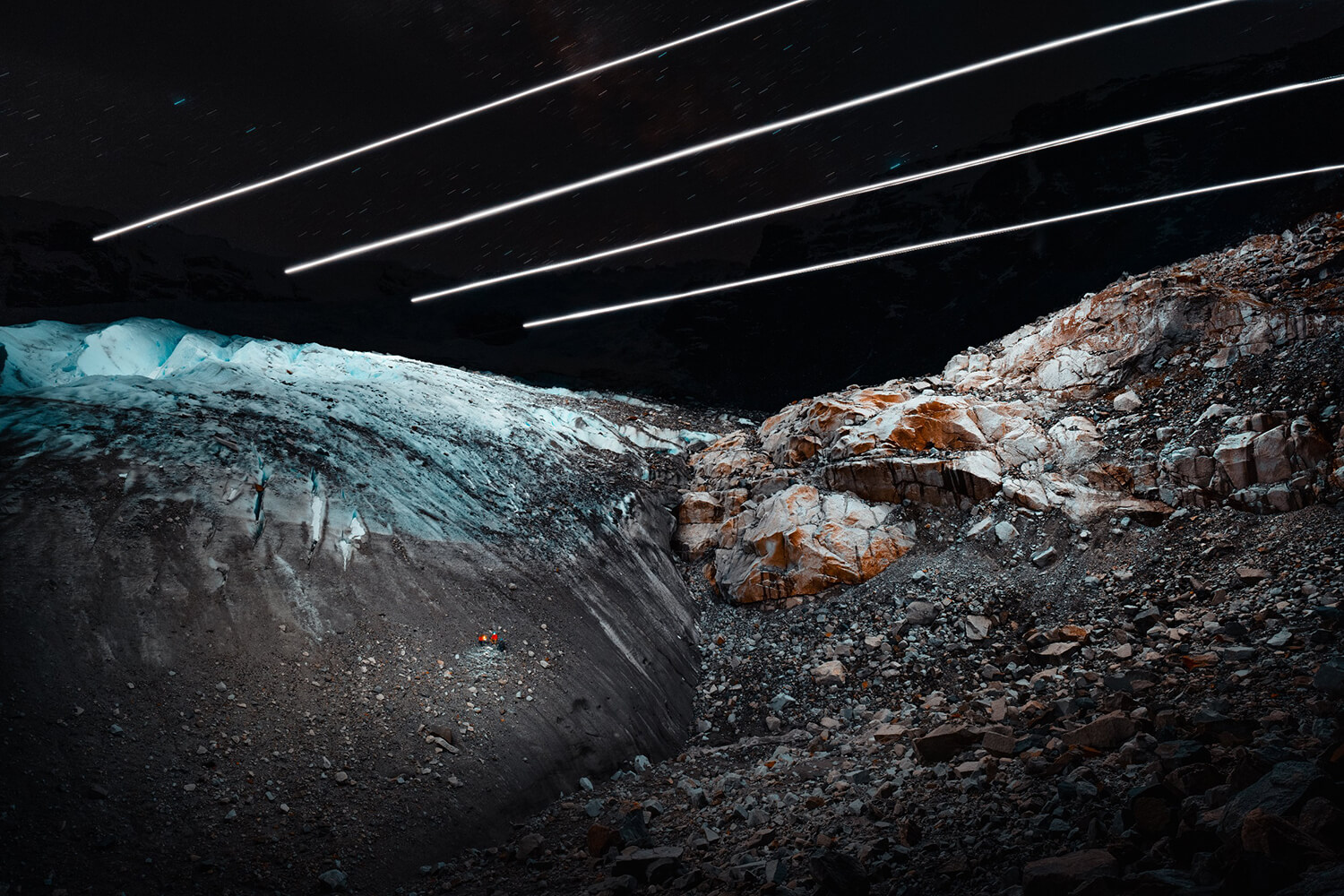

Liam Man won 1st Prize in our recent Planet Earth competition with an image judge Corey Arnold described as “complex and stunning, with an element of mystery that transports us into an alternative world.”

Characteristic of Liam’s broader work — poetic, ambitious scenes crafted with drones and light painting that speak to the immense beauty of the natural world — it has a remarkable story behind it, one he reveals in the questions we put to him. Find out more about Liam’s background, his approach, his realization he needed to explore a different form of landscape photography, and where he dreams of photographing next…

Liam, congratulations on winning our Planet Earth competition! Please introduce yourself in a few words…

My name is Liam Man, a photographic artist and light painter based in the United Kingdom. Through aerial light painting, I explore the intersection of art, technology and the natural world. My practice is guided by questions of memory, perception, and the human impact on fragile environments such as glaciers.

It’s a remarkable image which judge Corey Arnold described as “complex and stunning, with an element of mystery that transports us into an alternative world.” Can you tell us a little more about the circumstances behind the shot? What goes into creating a shot of this complexity?

In March 2023, a freak snowstorm was forecast to hit Scotland with just 24 hours’ notice. I had waited four years for the perfect conditions, so I drove the 1,000 kilometres from the south of England for this one image.

By the time I arrived at around midnight, the Old Man of Storr was still surrounded by a heavy blizzard. I began the climb through darkness, struggling to follow the path beneath the snow. When I finally reached the location, the conditions were still too severe to fly the drone.

Then suddenly, the storm broke and the winds fell silent. That unexpected change brought a rush of energy and focus. I launched the drone, and turned on the custom-built lights, cutting through the darkness and illuminating each pinnacle of the Old Man of Storr. At the same moment, the moon emerged from the horizon, glowing warmly through the hazy ice-filled air. Thirty minutes later, the blizzard returned and the landscape was lost again.

It’s also indicative of your work more generally – dramatic night-time landscapes, often incorporating light painting, that speak to the beauty and vulnerability of the natural world. What first drew you to these themes and techniques?

I come from a background in traditional landscape and tourism photography. Over the years, I’ve been fortunate to visit many extraordinary places. While undeniably beautiful, these locations were often among the most visited, and the human impact on them was hard to ignore. Empty bottles, food wrappers and eroded paths made it clear that many landscapes had been reduced to simple backdrops for selfies and travel photography.

I wanted my images to stand apart from this noise. To change how we perceive the planet and to encourage people to value and protect the hidden beauty that surrounds us.

LIAM’S WINNING PLANET EARTH IMAGE

And how do you go about scouting locations, deciding on the lighting effect you’d like to achieve and so on?

Scouting is the most important part of my process. I usually arrive a day early and walk the landscape in daylight, which allows me to visualise a composition that would be impossible to see at night. Once the framing is set, the lighting follows naturally. The shapes and forms of the landscape suggest how they want to be illuminated. In practice, I apply the same principles as in studio portraiture or product photography, balancing key, rim and fill light to reveal depth and character.

How you work – at the intersection of art and technology, for example building your own drone lighting rigs – is fascinating. Is it a solo endeavour or do you collaborate with others? And are there other artists working at this intersection who inspire you?

Most of the pre- and post-production is a solo process, but on location I like to bring at least one person with me. Many of the places I work in are remote, and having someone there for safety is always important. For this image in Scotland though, it was a solo expedition. Once I saw the forecast, there was simply no time to bring anyone along.

There are many people who have experimented with aerial light painting, and I am fortunate to count some of them as my friends and colleagues. But I rarely look to this field for inspiration. Instead, I tend to draw ideas from other genres; high-end fashion and sports photography for lighting, and environmental documentary photographers for storytelling. Jimmy Nelson, for example, is someone whose philosophical motives and approach to narratives has influenced me.

I wonder if you can talk us through a particular favourite shot of yours? Perhaps a recent one that was especially hard won or you’re especially proud of?

My favourite photograph from the past year is Ring of Fire and Ice, captured on 2 October 2024. On that date, an annular solar eclipse passed over Patagonia, Chile. As part of my Icebreaker project, it was a once-in-a-lifetime chance to photograph an eclipse from the surface of a glacier.

The expedition was entirely self-funded, making it a high risk expedition. I assembled a team of 10–15 people and we travelled to Glacier Leones, a remote site that required a 10-kilometre hike and a boat crossing of a glacial lagoon just to reach the ice front. We camped there for five days, scouting the glacier for the perfect location.

On the day of the eclipse, we worked with two local ice climbers and guides who ascended a ridgeline. We aligned their silhouettes with the eclipse overhead, and used a drone-mounted light to illuminate the glacial landscape, restoring depth and detail to the scene.

LIAM’S FAVORITE SHOT

Having shot in places such as Iceland, Chile and Switzerland, where else is on your bucket list? Are there particular environmental stories or locations you’d love to document?

I have what feels like an endless bucket list of locations. Every time I find a place that inspires me, I pin it on Google Maps – and by now the map looks almost diseased with markers.

Having focused on glacial landscapes and polar conditions over the past few years, I would love to go in the opposite direction and create a project on deserts. The rock formations and crystal-clear night skies would be a dream to work with.

What’s the best piece of advice you’d pass on to your younger self if you could?

I would tell myself to be fearless. The work you want to make takes time and motivation, and the path isn’t always clear. Keep experimenting, keep showing up, and trust that the voice you’re looking for will emerge. Believe in yourself sooner, start earlier, and give yourself the freedom to make mistakes.

And finally, what’s next? What will you be working on for the rest of 2025?

For the rest of 2025 I’ll be continuing activities relating to my “Icebreaker” project. In September I had the amazing opportunity to present this work in a solo exhibition at the UN World Expo in Osaka, Japan, and I am now exploring international venues for a touring exhibition to share the work more widely and highlight the fragility of sub-zero environments.

At the same time, I am planning new projects at further location and I am sure there will be more supernatural aerial experiments in the near future.