INTERVIEW

In the Inbetween

WITH ELIÉZER SENA

AN INTERVIEW WITH ELIÉZER SENA

“Up until last year, I’ve never felt like a real artist. My income comes from commercial photography, and I’ve always viewed myself as a sell-out…choosing money over substance, and though I was still shooting personal work, I seldom shared it. It’s really challenging work, returning to my inner artist, but it’s been very rewarding to let go of old beliefs and habits.”

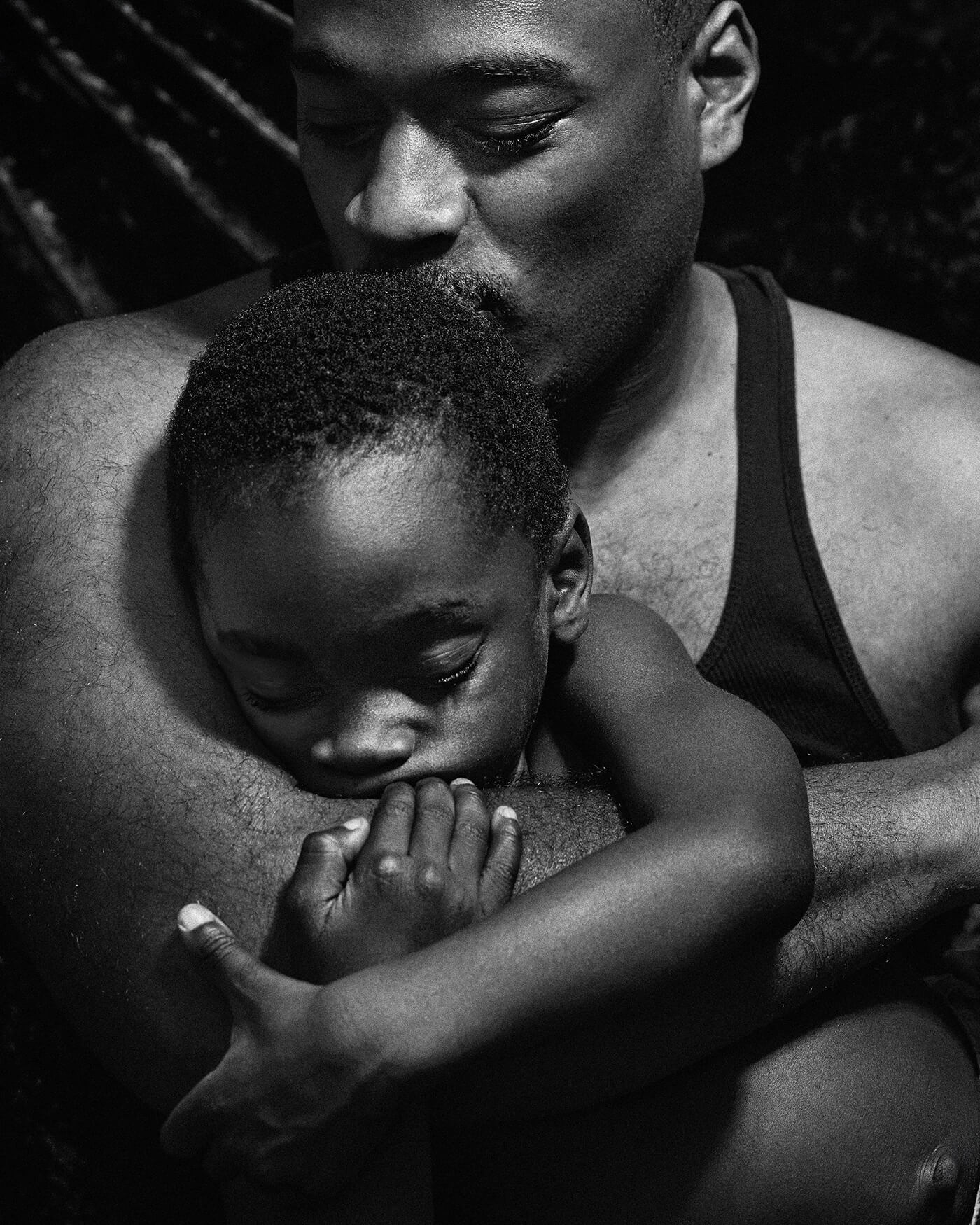

Eliézer Sena won 1st Prize in our recent Black & White competition with a tender portrait that captivated judge Marcin Ryczek with “its extraordinary delicacy”. Shot in response to the political and racial unrest in 2020, and the Black Lives Matter movement that grew from it, it is both a beautiful image and one charged with meaning, telling a different story to the black stereotypes that are pushed on us – a masculinity of love, care and affection.

Keen to learn more about Eliézer’s intentions, as well as his background, his inspirations, and how he navigates the push and pull between commercial and personal work, we put some questions to him…

ELIÉZER’S WINNING CITIES IMAGE

RAHEEM AND RUEL I

Eliézer, congratulations on winning our Black & White competition! Please introduce yourself in a few words…

Thank you so much! My name is Eliézer. I normally go by Eli, as most English speakers cannot pronounce my name correctly. BUT I’m slowly reclaiming my birth name, regardless of it being hard to pronounce. I am Brazilian, I’m an immigrant, I’m gay, and I love telling stories.

Tell us a little about your route into photography… You describe your style as one built from layers of cultural memory, diasporic rhythm, and life in motion. Tell us more about that…

As an immigrant growing up in one of the most underfunded cities in the state, where I expected to be met with white Americans, but instead was met with a plethora of every kind of immigrant, every color but white, I felt like like I had a completely wrong idea of what America would be like. I learned Spanish before I learned English. And even after I learned to speak English, I could not spell, I could not write. I’ll never forget testing to get out of ESL, when the teacher corrected me over and over and over again my pronunciation of “Salmon.” “The L is silent!” she would yell repeatedly. To this day, I think of her face anytime I hear someone say “saumon.” So in a way I’ve always felt othered. First because my name was different, then because of how I spoke, then because I was gay. And then because I didn’t know if I was black or white.

When I was introduced to analog photography in high school, it felt like it was a portal into another world. I would spend all afternoon in the dark room working on prints. It was an escape. But it was decades before I realized that my photography was art. In the effort to make it out of poverty, I completely forgot what it meant to be an artist, and devoted all my efforts into surviving the financial hardship I’ve always known. That is why my work touches on layers of cultural memory, diasporic rhythm, and life in motion… it’s my lived experience. It’s all I know. I remember Brazil, but don’t know exactly what it means to be Brazilian. I have African heritage, grew up eating West African food, but don’t know exactly what the black experience is like. I moved to America at nine years old, yet I don’t quite fit in as an American. I’m constantly in the in between, and finally learning to belong instead of fitting in.

Your winning image was borne from the political unrest and Black Lives Matter movement of 2020. It’s a tender and empathetic response to injustice, and one our judge Marcin Ryczek described as having “extraordinary delicacy”. Can you tell us a little bit about the experience of working with Rahim and Ruel on it?

At the time I created these portraits, I was already feeling very numb to all the violence I kept seeing in the news and social media. It affected my work, my relationships—I was either ready to spend days in bed, or fight anyone who had anything to say other than Black Lives Matter. Why couldn’t people see the tenderness of black men? Why did people believe narratives they saw on TV and social media so easily? It was a concept that felt clear to me because black tenderness shouldn’t require a photo of a black father kissing his son. The idea that absent fatherhood in the Black community stems from racism, over-policing, and surveillance is supported by research showing how systemic issues, criminal justice involvement, and discriminatory policies create barriers to fatherhood and family stability, even though Black fathers are heavily involved.

Raheem was the first person I thought of when I dreamed up this project. I met him as a single father, caring for his baby, before she was 1 years old. I remember the time when I gave him a ride home after prayer night at church. It was us two, and his baby daughter. We sat in the backseat of my car, both not knowing what to do about this little baby’s cry and discomfort. How could we? We were both kids. I saw him grow into a wonderful father. As he married and had more children, his tenderness and kindness only seemed to grow. The shoot was very simple, just him and his son sitting on a stool, with a velvet backdrop. No wardrobe, no props. I didn’t ask them to pose, I just photographed them interacting with each other: Raheem picking him up, Ruel on his lap, comforting him as Ruel had no interest in sitting for a photo shoot longer than 2 minutes. The final photo happened during one of these moments, when Ruel was growing tired, and Raheem trying to settle him on his lap. The way Ruel holds on to his dad, nestling his face in his arm, kissing it, and Raheem’s tender kiss on Ruel’s head was a perfect display of fatherly love and acceptance. It really touched me, and I knew it would touch others as well.

CHACHA

RAHEEM AND RUEL II

RAEZEL

You’ve worked with some pretty large brands – Blue Diamond, Crocs, Samuel Adams, Canada Dry – creating work that’s bold, playful, colorful. What does a typical assignment look like? And how do you manage the push and pull between client brief and your own aesthetic wants?

This weighs on me more than you can imagine. It took years for me not to feel like a sold-out artist, catering to consumerism via commercial jobs for the betterment of my career. I admit, shooting commercial work has allowed me the luxury to live existentially. But now that I have, I can’t ignore my calling, which is to tell authentic stories, and share myself through them with the world. In every commercial project I am invited to, I make it an effort to celebrate my Brazilian and mixed culture whenever possible, whether through casting, location, or propping. I try to create narratives that matter, that tell a story not only to sell something, but to connect. Unfortunately, though, these creatives tend to get watered down by execs who are only interested in selling their product. I don’t think I have enough influence in the industry yet, to keep pushing real stories in the way I envision. Soon, though. At the end of the day, I have to look at it as a job, not necessarily art. And if my creativity gets killed, or my aesthetic needs to be reduced to something more digestible, I have to accept it.

I generally work with a team of creatives on a typical assignment, who all help the vision come to life. My job begins by interpreting the client brief, and creating mood boards and a suggested shot-list. Often times, I push the creative outside the box, expecting some feedback to make it more safe. Sometimes I am pleasantly surprised, and we end up shooting a bold and colorful campaign. With the help of 3-20 people on set (depending on scope) we often shoot for speed. But if we have a solid creative foundation, moving quickly through the set feels natural.

Is there a bucket list campaign or collaborator you’d love to work with or on?

No particular collaborator, but I’d love to shoot a project or campaign in Brazil. I’m fortunate to work with the brands that I have, but I am more inclined to feel connected to the brand if it’s a sustainable one that doesn’t exploit underprivileged communities, the way sugary beverages and snacks do. It’s also been a dream of mine to shoot a cookbook. Food is one of those things that can bring anyone together, and to be able to make art with it so that others can make it too would be extremely fulfilling.

And having shot across the US, India, Iceland, Ireland, and your home country of Brazil, what about a dream location?

Honestly, there is no other dream than to make my beautiful and welcoming culture accessible and available to everyone. I love where I come from. For so long I felt so disconnected from Brazil. Leaving when I was nine years old, and rarely having the opportunity to go back, I eventually lost touch with my culture, and even my language. I fell in love with Brazil again the last time I was there. It’s where my Portuguese comes alive again, and I can feel the joy and peace entering my body as soon as I breathe in that tropical air. Of course I’d love to keep traveling and photograph the world, but there is truly nothing like being home. Next on my list is Morocco. I can’t wait for the stories I’ll uncover over there.

Could you tell us the story behind one of your favorite images to date?

Absolutely [see image below]. It was 2020, and I was in India with a good friend. We were there to document Holi in Mathura, where the heart of this celebration is. We stayed for a total of 3 weeks as we traveled the country. Though I love the photos I shot during Holi, my favorite one came days later when we visited the monkey temple in Jaipur, famous for its many resident monkeys. On our way up to the temple we saw a small nomadic family living in tents off the side of the road. I wanted to stop and hang out with them for a while, but we didn’t want to miss the sunrise at the temple. On our way back down, the family was still there. A mother and father, their small children, and a few other adults. As I approached them, the mom immediately ran inside her tent and fetched a woven basket from underneath one of the beds. From it, she pulled out a black cobra and insisted I put it around my neck. After my initial scare and their laughs, I refused many times. And to show that the snake was safe, she put it around her young son’s neck. The photo I took of him, as the snake coiled around his neck and pressed its face against his, his little sister sitting in the background, their belongings everywhere, and his piercing gaze, is my favorite image to this day.

ELIÉZER’S FAVORITE SHOT

And who or what inspires you, outside of the genre of photography?

These days, it’s been Julia Cameron, and her book The Artist’s Way. The book is about returning to your inner artist, a creative rehab of sorts. Submitting my work to this competition was a result of that. Up until last year, I’ve never felt like a real artist. My income comes from commercial photography, and I’ve always viewed myself as a sell-out…choosing money over substance, and though I was still shooting personal work, I seldom shared it. It’s really challenging work, returning to my inner artist, but it’s been very rewarding to let go of old beliefs and habits.

What’s the best piece of advice you’d pass on to your younger self if you could?

You don’t have to be anything else other than who you already are. You’re perfect just as is. No need to embellish anything, no need to exaggerate, no need to over-explain. Simply being is enough.

And finally, what’s next? What will you be working on in 2026?

Oof, that’s a loaded question. Honestly, I don’t know. I have plans, ideas, goals for more projects, and I tend to get discouraged when things don’t unfold in the timeline I had hoped. I’m letting go of that though. As a queer survivor of toxic religion, I’d love to collaborate with other queer folk who grew up in the church, who also had to carve their way out of survival and into a thriving queer, free life. Maybe it’ll turn into a book, or a zine, I don’t know. But I know my experience isn’t unique. Queer youth who face high levels of family and religious rejection are significantly more likely to attempt suicide.

If I had access to stories of gay men and women like this as a young person growing up in church, maybe I could’ve avoided years of inner turmoil, maybe I would’ve never married a woman and hurt her in the process, maybe I would’ve never had ideations to end my own life, and maybe I wouldn’t have waited until I was 29 to come out of the closet. I’m not alone in this—queer youth facing high levels of family and religious rejection are significantly more likely to attempt suicide. For lesbian and gay youth, higher importance placed on religion increases the odds of recent suicidal thoughts by 38%, with this effect being even higher for lesbians alone at 52%. These aren’t just numbers to me – they represent real people, real pain, and real lives that could be saved through visibility and acceptance.