INTERVIEW

Outsider Stories

WITH DAN GIANNOPOULOS

An interview with Dan Giannopoulos

“Sometimes it’s about people being misunderstood, sometimes it’s a celebration of things that have brought disparate people together. But mostly I explore these communities because I think I’ve always seen myself as an outsider.”

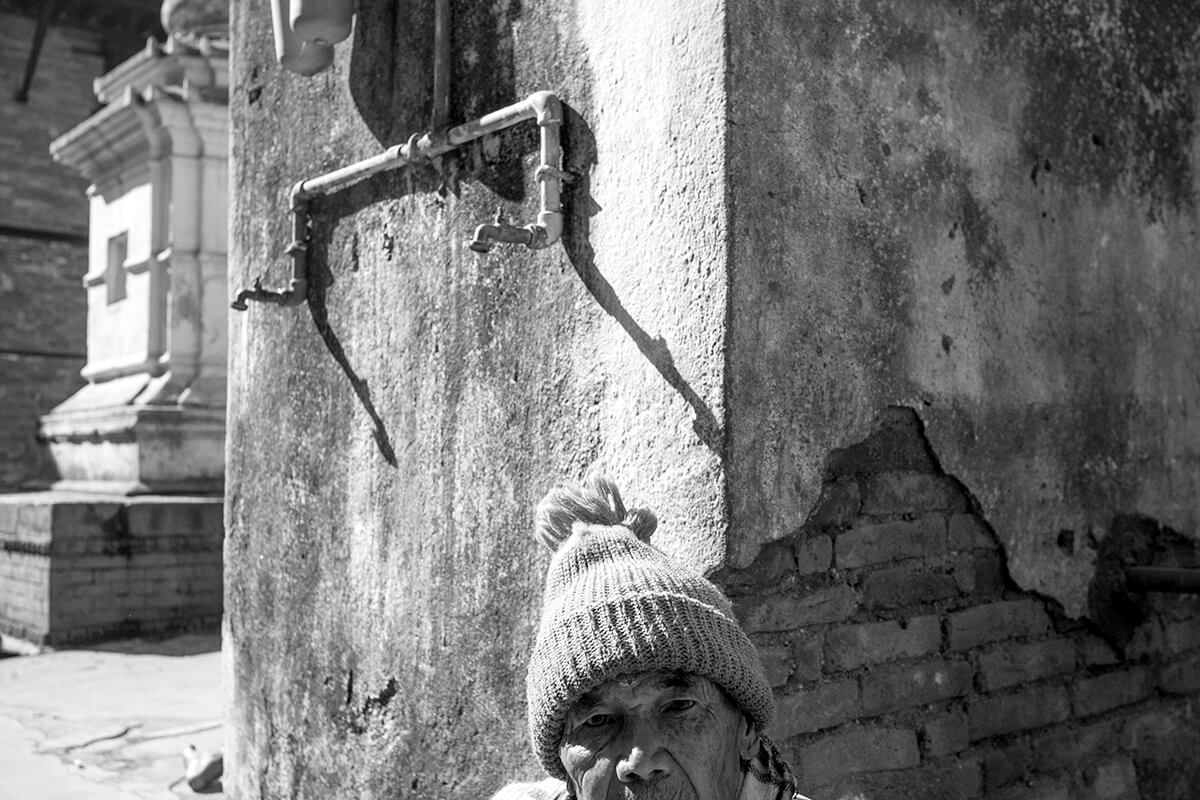

Dan Giannopoulos won our second theme of Life Framer Edition V – The Human Body – with a challenging image of an elderly man at a nursing home in Nepal. Our judge, Roger Ballen, praised it for its impact, describing it as “a very real image of the extremes the human body can endure and the state of humanity”.

Keen to know more we put some questions to Dan, asking him about the image and series, photojournalistic ethics, and why he’s so fascinated by documenting outsider communities…

Hi Dan. Congratulations on winning our theme ‘The Human Body’ judged by Roger Ballen. What did you make of his comments on your image?

The comments echoed the feelings I have about this image. I had entered the image and others from the same series because I felt like they would challenge the theme. It’s a tragic image of what aging can do to the human body and also an exploration of how bad care for the elderly can be in some places.

Can you tell us a little bit more about the image, and what it means to you? I understand it comes from the series The Orphaned Elderly of Kathmandu – tell us about that.

The series documents a Social Welfare Home for the Elderly that sits on the outskirts of Kathmandu, Nepal. The home, founded in the late 1980s, houses approximately 240 elderly residents who have been abandoned by their relatives and who have no suitable guardian or carer. After Nepal became a secular republic in 2008 the country saw a rapid decline in suitable healthcare provision, especially in rural areas.

In the past elders in Nepali community were treated with respect and were cared for by their children and families until their passing. With the increase of western influence on Nepali culture and a gradual shift of familial structures to a more nuclear setup, family elders are now seen as more burdensome than in times gone by. With a lack of understanding about mental health issues, families are increasingly unable and often unwilling to deal with the complexities of their older relative’s illnesses and as a result often abandon them, leaving them to fend for themselves.

I have always found it an unsettling image to view because I still vividly remember the scene. He was deeply confused. He looked almost childlike laying on the floor. I shot about five frames before I went to help the man up. It wasn’t until I did this that I was aware that he was covered in flies and had soiled himself. There were many scenes like this at the home. Nearly all the residents at the home were abandoned by their families. Mostly because they had physical and mental health conditions that their families struggled to deal with (understanding of conditions such as dementia in Nepal is very low especially in rural communities where access to decent healthcare is relatively non-existent.)

Dan’s winning for the theme ‘THE HUMAN BODY’

How did that series come about? How did you hear about the Pashupati Briddhashram home, and what was the process from thereon? Did you have a specific vision at the beginning, or did it evolve as you went?

I had completed a project shortly before heading to Nepal which had explored my grandfather’s stroke and subsequent Dementia diagnosis. That situation was obviously distressing to me, but I had documented his deterioration for a long time, partly as a way for me to process slowly losing someone that I loved and partly to document how dementia impacts on the sufferer and their family. After completing that work I had become interested in how other societies treated their elderly and I began researching care homes in Nepal, of which there seemed to be very few. I made arrangements to visit with Pashupati Briddhashram Social Welfare Home and I was immediately shocked at the conditions these people lived in. And knew it was an important story to explore.

You chose to shoot this series in black and white. What was the rationale for that?

At the time I preferred to shoot in black and white. I had shot the project with my grandfather in black and white and felt as though this was a continuation of that work, or subject.

What’s your over-arching feeling having documented the Pashupati Briddhashram home? Is it a subject you’d like to return to, or has it opened up other subjects in Nepal that interest you?

I’m interested in continuing to shoot work on treatment of the elderly and I would like to go back to Pashupati Briddhashram to see what changes have been made since I was there last and to possibly volunteer. I have travelled extensively and my mind often wanders back to Nepal. It is a country that I have a strong connection with and there are many stories I would like to explore there.

Photographing vulnerable people is not without controversy – the neutrality of documenting something ‘as it is’, or even the benevolence of exposing an injustice to a wider audience can be muddied by ideas of exploitation. How do you respond to that as a documentary photographer? Is it something you’re very aware of? Is it something you get challenged on?

I’ve always struggled with this aspect of photojournalism. I try to shoot work in as respectful a manner as I possibly can. I always aim to preserve the dignity of people I photograph. With respect to the image awarded here, I wanted to show the tragedy of the scene – what age, abandonment and severe illness can do to the body – but without having this person be identifiable. There is the argument that the moment I entered this into an award that carried a substantial cash prize the spirit of photojournalism is tainted. I guess that argument is made on the assumption that the awarded money isn’t directly invested into producing more work. I always adhere to the ethics of photojournalism and more importantly the ethics of being a decent and kind human being.

I’ve been challenged on my photography many times but the stories I have chosen to document are sometimes challenging, so I expect and welcome discussion about the stories – that’s part of the reason I do it.

You describe yourself as being interested in photographing outsiders and fringe communities, and have undertaken projects exploring ‘bikelife’, the rise of the far-right in the UK, drug culture and the metal scene – sometime with a candid approach, and other times through portraiture and documentation of objects. What are you looking for with each of these projects? Is it something that hasn’t been very exposed, or that is misunderstood? Is there a particular community you’d love to document?

Sometimes it’s about people being misunderstood, sometimes I see these stories as a celebration of things that have brought disparate people together. Sometimes it’s a combination of multiple themes. But mostly I explore this because I think I’ve always seen myself as an outsider. I was bullied as a kid and spent a lot of my childhood feeling pretty isolated. As I got older and began travelling a lot I realised that being an outsider wasn’t actually that bad, being somewhere where you didn’t quite fit in was oftentimes the exact thing that made a place or an experience more meaningful.

I’m keen to get back to shooting my Full Metal Jackets project which explores the UK’s Battle Jacket community. I started the project just before leaving for a year in Central America and I’ve been eager to meet more people and see more elaborate battle jackets and hear more stories about how these items of clothing bring people together.

What are the things that aspiring documentary photographers might not think about? What lessons have you had to learn? What advice could you give?

I think first and foremost this sort of work is about telling untold stories in engaging ways. Honouring the people that let you into their lives for sometimes brief, sometimes long periods of time. Try to tell the story as best you can with as much respect for them as you can. Sometimes this takes time. I spent over two years photographing the UK Bikelife community and could easily have spent much longer. I’m still learning how to do this myself. But the older I get the more I realise that the best work you shoot is most often the stories within a few miles of your home. The stories that you can spend time on and are part of your everyday life.

And finally, I understand that you’re currently in South America. What are you working on?

I am actually back in the UK now developing projects here, but still working on other projects that I started in Central America. Currently I’m working on a long-term project in El Salvador on the impact of gang violence and efforts made by the government and the church to rehabilitate ex-gang members.

All images © Dan Giannopoulos

Follow him on Instagram: @dan_gian and see more at www.gianphotography.com